EuroBioC2025 OSTA Workshop

Source:vignettes/seq-workflow-visium-hd-cell.Rmd

seq-workflow-visium-hd-cell.RmdWorkflow: Visium HD cell-level

Authors: Yixing E. Dong1, Ellis Patrick2.

Last modified: 20 January, 2026.

Preparation

Dataset

The relevant data by Oliveira et al. (2025) are stored on Open Science Framework, and can be downloaded as delayed format cached on your laptop through OSTA.data:

library(OSTA.data)

id <- "VisiumHD_HumanColon_Oliveira"

pa <- OSTA.data_load(id)

dir.create(td <- tempfile())

unzip(pa, exdir=td)

list.files(file.path(td, "segmented_outputs"))

#> [1] "cell_segmentations.geojson" "filtered_feature_cell_matrix.h5"

#> [3] "nucleus_segmentations.geojson" "spatial"We prepared a reader for Visium HD segmented output at

./vignettes/utils.R.

Update (January 2026): Pull requests branched from

this reader have been merged into the VisiumIO and

SpatialFeatureExperiment packages.

R / Bioconductor packages used

Bioconductor: Biobase, BiocStyle, Banksy, CARDspa, DropletUtils, GenomeInfoDb, ggspavis, OSTA.data, S4Vectors, scater, scran, scuttle, SingleCellExperiment, spacexr, SpatialExperiment, SpatialFeatureExperiment, spicyR, SpotSweeper, Statial, Voyager

CRAN: dplyr, ggplot2, grDevices, grid, here, igraph, magick, pals, patchwork, pheatmap, plotly, rlang, sf, tidyr, tidySpatialExperiment, tidyverse

Workshop goals and objectives

The key steps of Visium HD data analysis are described in this workshop, along with diverse visualizations of the methods used. The goal is to help beginner bioinformaticians working with Visium HD data become familiar with each step involved and complete a standard analysis pipeline from start to finish.

Learning goals

- Learn how to analyze Visium HD data with cell segmentation output

- Understand the key steps and methods for deriving biological insights

- Create aesthetic visualizations of Visium HD data using existing R packages

Learning objectives

- Read Visium HD segmentation output data as a

SpatialFeatureExperimentobject - Understand spatially aware quality control metrics

- Perform label transfer from single-cell reference data to spatial data

- Identify spatial domains and marker genes for each region

- Visualize Visium HD data as polygons or cell centroids

- Extract morphological metrics from cell polygons and make inference

- Conduct spatial analysis in a tissue slice

Introduction

As of June 2025, Visium HD enables direct output of H&E-segmented

cell-level data from SpaceRanger

v4. This automation removes the need for an additional segmentation

tool, such as bin2cell. Since biologists often find

cellular units more intuitive for deriving insights, this output may

attract more interest than bin-level data. However, bins outside cell

boundaries can still provide valuable information for many research

topics in the tumor microenvironment. In this workflow, we will

demonstrate several cell-level analysis steps using the same dataset,

subsetted to the same region, as in the Sequencing-based platforms -

Workflow: Visium HD bin-level chapter of the OSTA book.

Dependencies

library(AUCell)

library(Biobase)

library(BiocStyle)

library(Banksy)

library(CARDspa)

library(dplyr)

library(DropletUtils)

library(GenomeInfoDb)

library(ggfortify)

library(ggplot2)

library(ggpubr)

library(ggrepel)

library(grDevices)

library(grid)

library(here)

library(igraph)

library(magick)

library(msigdbr)

library(OSTA.data)

library(pals)

library(patchwork)

library(pheatmap)

library(plotly)

library(rlang)

library(S4Vectors)

library(scater)

library(scran)

library(scuttle)

library(sf)

library(SingleCellExperiment)

library(sosta)

library(spacexr)

library(SpatialExperiment)

library(spatialFDA)

library(SpatialFeatureExperiment)

library(spatstat)

library(spicyR)

library(SpotSweeper)

library(Statial)

library(stats)

library(tidyr)

library(tidySpatialExperiment)

library(tidyverse)

library(Voyager)We source the reader defined in utils.R and specify

alias for plotting themes.

source(here::here("vignettes/utils.R"))

# ggplot theme alias

center_title <- theme(plot.title = element_text(hjust = 0.5))

no_legend <- theme(legend.position = "none")

gradient_theme <- theme(plot.title = element_text(hjust = 0.5),

legend.title = element_blank(),

legend.key.width = grid::unit(0.5, "lines"),

legend.key.height = grid::unit(1, "lines"))

thin_discrete_legend <- theme(legend.key.size = grid::unit(0.5, "lines"))

enlarge_legend_dot <- guides(col=guide_legend(override.aes=list(size=3)))

common_args_heatmap <- list(cellwidth=10, cellheight=10,

treeheight_row=5, treeheight_col=5)Load spatial data

Output files from SpaceRanger v4 are located in

/segmented_outputs folder, following the expected structure

described in the Background - Importing data chapter of the

OSTA book.

id <- "VisiumHD_HumanColon_Oliveira"

pa <- OSTA.data_load(id)

dir.create(td <- tempfile())

unzip(pa, exdir=td)We read the Visium HD cell-segmented data into a

SpatialFeatureExperiment object.

vhdsfe <- readVisiumHDCellSeg(td, res = "hires")

#> Reading layer `cell_segmentations' from data source

#> `/tmp/RtmpoiuzOa/file8967cdcc18/segmented_outputs/cell_segmentations.geojson'

#> using driver `GeoJSON'

#> Simple feature collection with 220704 features and 1 field

#> Geometry type: POLYGON

#> Dimension: XY

#> Bounding box: xmin: 40587.5 ymin: -28.8 xmax: 65202.7 ymax: 22701

#> Geodetic CRS: WGS 84

vhdsfe

#> # A SpatialExperiment-tibble abstraction: 220,703 × 8

#> # Features = 18132 | Cells = 220703 | Assays = counts

#> .cell Sample Barcode sample_id pxl_col_in_hires pxl_row_in_hires

#> <chr> <chr> <chr> <chr> <dbl> <dbl>

#> 1 3 /tmp/RtmpoiuzOa/fi… cellid… sample01 3555. 3571.

#> 2 4 /tmp/RtmpoiuzOa/fi… cellid… sample01 3551. 3569.

#> 3 5 /tmp/RtmpoiuzOa/fi… cellid… sample01 3557. 3570.

#> 4 6 /tmp/RtmpoiuzOa/fi… cellid… sample01 3549. 3570.

#> 5 7 /tmp/RtmpoiuzOa/fi… cellid… sample01 3565. 3570.

#> 6 8 /tmp/RtmpoiuzOa/fi… cellid… sample01 3553. 3571.

#> 7 9 /tmp/RtmpoiuzOa/fi… cellid… sample01 3557. 3573.

#> 8 10 /tmp/RtmpoiuzOa/fi… cellid… sample01 3562. 3572.

#> 9 11 /tmp/RtmpoiuzOa/fi… cellid… sample01 3571. 3571.

#> 10 12 /tmp/RtmpoiuzOa/fi… cellid… sample01 3546. 3570.

#> # ℹ 220,693 more rows

#> # ℹ 2 more variables: pxl_col_in_fullres <dbl>, pxl_row_in_fullres <dbl>

#>

#> unit:

#> Geometries:

#> colGeometries: centroids (POINT), cellSeg (POLYGON), updatecentroids (POINT), updatecellSeg (POLYGON)

#>

#> Graphs:

#> sample01:To keep the runtime low, downstream analyses are performed on a subset region corresponding to 16 µm bins, representing approximately 1/64 of the full data coverage area. We restrict the analysis to the same region used in the OSTA book.

vhdsub <- subsetVisiumHD(vhdsfe,

xmin = 4214.937, xmax = 4465.761,

ymin = 2979.286, ymax = 3211.817)Because the analysis is limited to this subset of the tissue, the

number of cells in the corresponding sf object is expected

to be reduced by roughly the same fraction, depending on local tissue

density.

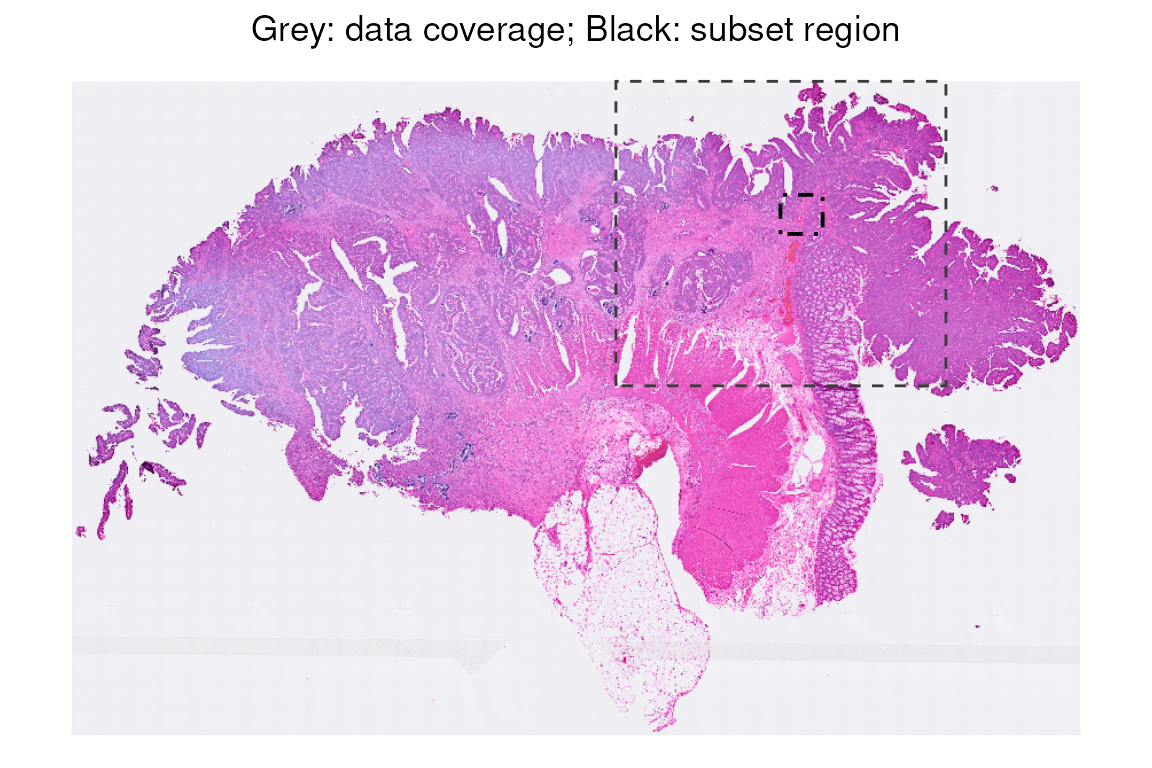

Show the subset region used for analysis:

plotImage(vhdsfe) +

plotBox(getBoxRange(vhdsfe), col = "#3b3b3b", lty = 2, lwd = 1/2) +

plotBox(getBoxRange(vhdsub), col = "black", lty = 4, lwd = 2/3) +

ggtitle("Grey: data coverage; Black: subset region") +

center_title

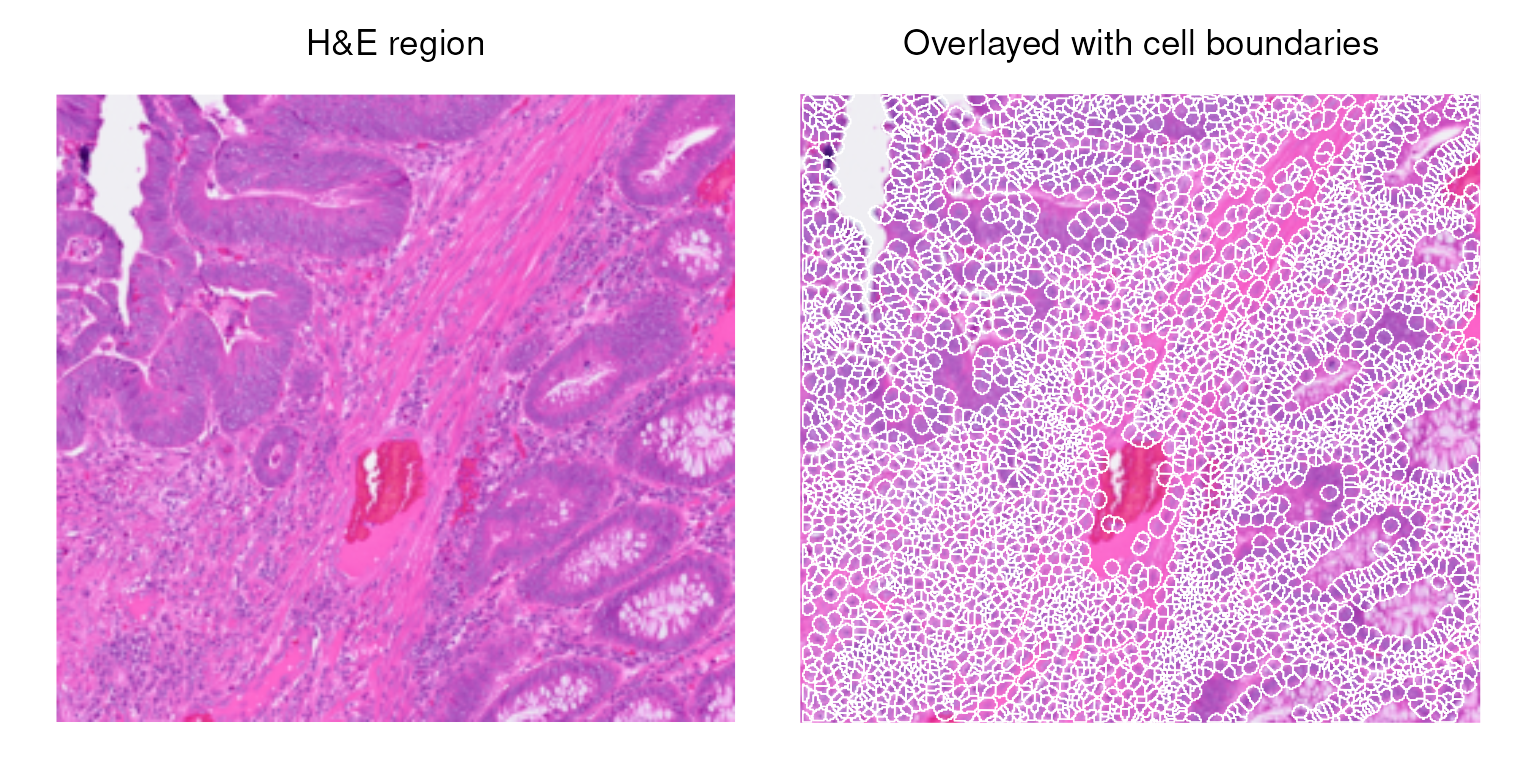

Plot cell polygons overlaid on the H&E image for this subset region (in black box). Here is an overview of the tissue subset that we will use throughout the workflow.

vhdsub$polygon <- 1

p0 <- plotImage(vhdsub, bbox = unlist(getBoxRange(vhdsub)))

p1 <- plotSpatialFeature(vhdsub, bbox = unlist(getBoxRange(vhdsub)),

features = "polygon", alpha = 0.1, fill = NA, color = "white",

colGeometryName = "updatecellSeg", image_id = "hires") +

no_legend

(p0 + ggtitle("H&E region") |

p1 + ggtitle("Overlayed with cell boundaries")) &

center_title

Which cells pass quality check?

Compute cell-level QC metrics using scuttle.

# Visualize library size to the polygons

sub <- list(mt = grep("^MT-", rownames(vhdsub)))

vhdsub <- addPerCellQCMetrics(vhdsub, subsets = sub)

vhdsub$log_sum <- log1p(vhdsub$sum)

CD <- colData(vhdsub) %>% as.data.frame()

head(CD %>% select(Barcode, sum, log_sum, subsets_mt_percent))

#> Barcode sum log_sum subsets_mt_percent

#> 84452 cellid_000084452-1 139 4.941642 3.597122

#> 84464 cellid_000084464-1 553 6.317165 2.169982

#> 84472 cellid_000084472-1 1218 7.105786 2.298851

#> 84476 cellid_000084476-1 1004 6.912743 4.681275

#> 84504 cellid_000084504-1 835 6.728629 5.029940

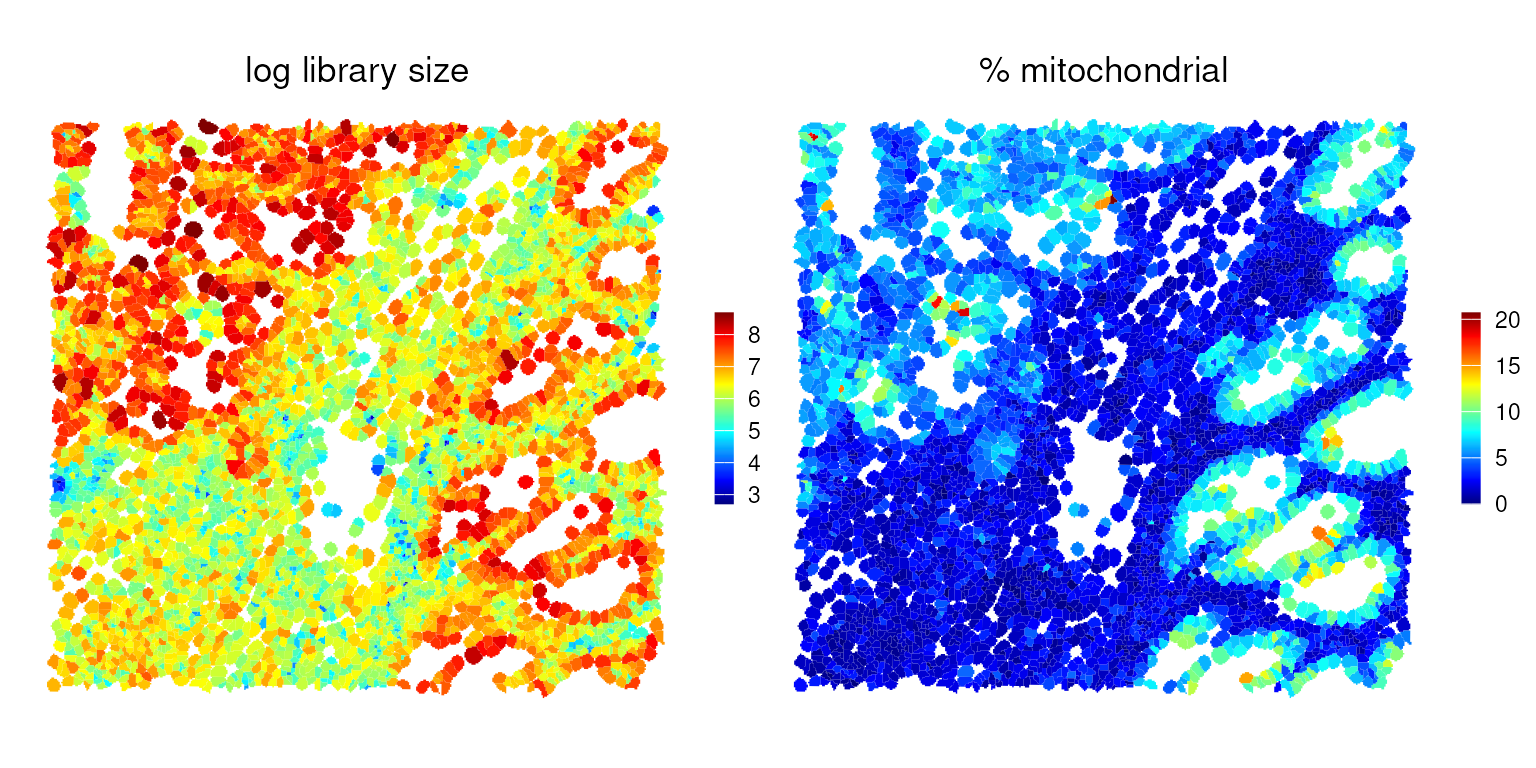

#> 84560 cellid_000084560-1 436 6.079933 2.981651Here is an overview of cells colored by their log library size and mitochondrial percentage.

p0 <- plotSpatialFeature(vhdsub, features = "log_sum",

colGeometryName = "updatecellSeg") +

ggtitle("log library size")

p1 <- plotSpatialFeature(vhdsub, features = "subsets_mt_percent",

colGeometryName = "updatecellSeg") +

ggtitle("% mitochondrial")

(p0 | p1) &

gradient_theme &

scale_fill_gradientn(colors = pals::jet())

SpotSweeper

SpotSweeper identifies outliers based on low log-library size, a low number of uniquely detected features, or a high mitochondrial fraction relative to the surrounding neighborhood:

vhdsub <- localOutliers(vhdsub, metric="sum", direction="lower", log=TRUE)

vhdsub <- localOutliers(vhdsub, metric="detected", direction="lower", log=TRUE)

vhdsub <- localOutliers(vhdsub, metric="subsets_mt_percent", direction="higher", log=TRUE)

vhdsub$discard <-

vhdsub$sum_outliers |

vhdsub$detected_outliers |

vhdsub$subsets_mt_percent_outliers

# tabulate number of cells retained vs. removed by any criterion

table(vhdsub$discard)

#>

#> FALSE TRUE

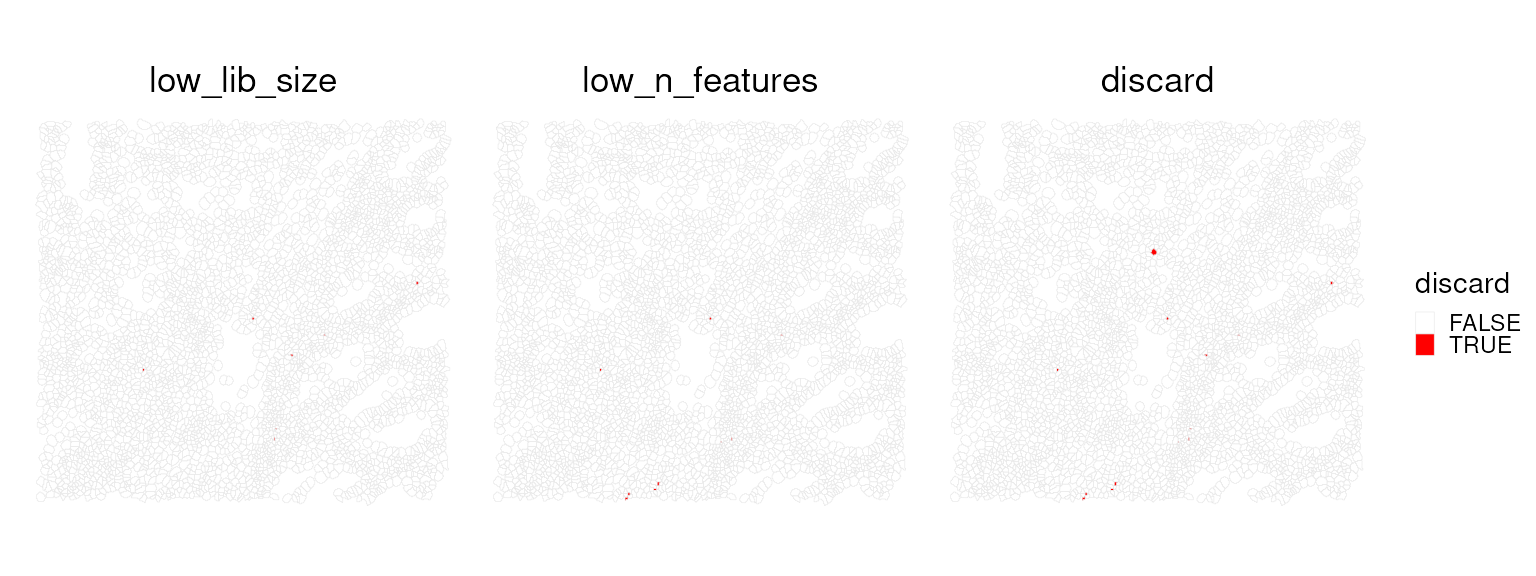

#> 4406 13We can visualize the local outliers identified by

SpotSweeper in a spatial context. However, they are

difficult to discern, as only a small number of relatively small cells

are flagged as outliers.

common_args_qc <- list(fill = NA, color = "grey90", linewidth = 0.1,

colGeometryName = "updatecellSeg")

p0 <- exec(plotSpatialFeature,

vhdsub, features = "sum_outliers", !!!common_args_qc) +

ggtitle("low_lib_size")

p1 <- exec(plotSpatialFeature,

vhdsub, features = "detected_outliers", !!!common_args_qc) +

ggtitle("low_n_features")

p2 <- exec(plotSpatialFeature,

vhdsub, features = "discard", !!!common_args_qc) +

ggtitle("discard")

p0 + p1 + p2 +

plot_layout(nrow=1, guides="collect") &

thin_discrete_legend & center_title &

scale_fill_manual("discard", values=c("white", "red"))

What type of cells do we have in this region?

Load reference

This Visium HD dataset includes matched scRNA-seq data from the same

tissue, which helps avoid tissue-specific and batch effects that often

complicate label transfer. The Level1 column contains

broad, interpretable cell populations that are well suited for

deconvolution and downstream interpretation. We use these labels to map

likely cell identities onto the Visium HD cells.

First, we load the data from the OSTA.data package.

## SCE ref

id <- "Chromium_HumanColon_Oliveira"

## Download the data for OSTA.data and unzip the files

pa <- OSTA.data_load(id)

dir.create(td2 <- tempfile())

unzip(pa, exdir=td2)

# read into 'SingleCellExperiment'

fs <- list.files(td2, full.names=TRUE)

h5 <- grep("h5$", fs, value=TRUE)

sce <- read10xCounts(h5, col.names=TRUE)

# add cell metadata

csv <- grep("csv$", fs, value=TRUE)

cd <- read.csv(csv, row.names=1)

colData(sce)[names(cd)] <- cd[colnames(sce), ]

# use gene symbols as feature names

rownames(sce) <- make.unique(rowData(sce)$Symbol)

# exclude cells deemed to be of low-quality

sce <- sce[, sce$QCFilter == "Keep"]We will use this single-cell dataset as a reference. It contains cell

annotations at two resolutions. First, let’s inspect the labels in

Level1.

# tabulate subpopulations

table(sce$Level1)

#>

#> B cells Endothelial Fibroblast

#> 33611 7969 28653

#> Intestinal Epithelial Myeloid Neuronal

#> 22763 25105 4199

#> Smooth Muscle T cells Tumor

#> 43308 29272 65626Spaces can make manipulating data tricky sometimes, so let’s replace them with underscores.

sce$Level1 <- gsub(" ", "_", sce$Level1)For speed, we down-sample to at most 1,000 cells per reference class. This preserves diversity within each class while keeping memory use and runtime manageable.

RCTD - Robust decomposition of cell type mixtures in spatial transcriptomics

There are many approaches for transferring labels from single-cell

data to spatial data. Here, we use spacexr

(i.e., RCTD) because it performs competitively in public

benchmarks (Sang-Aram et al. (2024); Li

et al. (2023); Gaspard-Boulinc et al. (2025)), explicitly models mixed

signals, and assigns each spatial unit a clear classification as either

a singlet or one of several doublet types.

RCTD was originally developed for spot-based platforms

such as 10x Visium, where each spot captures RNA from multiple cells.

The method models the observed counts in each spot as a mixture of

reference cell-type expression profiles and uses a likelihood-based

framework to estimate non-negative weights for each candidate cell type.

It then compares a singlet model with a doublet model to determine

whether the counts are best explained by one or two cell types. In

addition, RCTD learns scale factors to account for

differences in platform characteristics and total RNA content,

facilitating robust label transfer across technologies (Cable et al. (2022)).

In our setting, we apply RCTD at cellular resolution

using segmented Visium HD data. Although each unit is intended to

represent a single cell, there are cases where the measured counts may

reflect contributions from multiple cell types. This can arise from

partial-volume effects at cell boundaries, segmentation errors, densely

packed regions, or local diffusion of transcripts. Running

RCTD in doublet mode remains useful in this context, as it

can flag such cases and provide a principled estimate of the most likely

composition. In practice, we expect most units to be classified as

singlets, with a smaller fraction of doublets that warrant closer

inspection or additional filtering.

Because running RCTD is computationally intensive, we

load a precomputed result for this workflow.

# data("rctd_result_level1.RData", package = "EuroBioC2025_OSTA_Workshop")

load(here::here("data/rctd_result_level1.RData"))!!! Do not run this in the workshop, as it will take 30 mins.

# ## Perform initial preprocessing of the visiumHD and single cell reference data

# rctd_data <- createRctd(spatial_experiment = vhdsub, # Our visium HD data

# reference_experiment = sce[, down_sample],# Down-sampled single cell reference

# cell_type_col="Level1", # We will use the Level1 resolution of cell types.

# UMI_min = 0) # To make things easier, we won't filter away cells that RCTD thinks are poor quality.

#

# ## Perform the deconvolution.

# rctd_result_level1 <- runRctd(rctd_data, max_cores = 4, rctd_mode = "doublet")

# # save(rctd_result_level1, file = here::here("data/rctd_result_level1.RData"))Note: RCTD includes internal quality control steps, so

we first check whether any cells were filtered out before running the

deconvolution.

dim(vhdsub)

#> [1] 18132 4419

dim(rctd_result_level1)

#> [1] 9 4418

setdiff(colnames(vhdsub), colnames(rctd_result_level1))

#> [1] "91874"

vhdsub$discard[colnames(vhdsub) == "91874"]

#> [1] TRUE

vhdsub$sum_outliers[colnames(vhdsub) == "91874"]

#> [1] TRUE

vhdsub$sum[colnames(vhdsub) == "91874"]

#> [1] 14

head(sort(vhdsub$sum))

#> [1] 14 18 19 19 22 23The spot labels are stored in colData() as

spot_class. This provides a quick quality check: observing

a majority of singlet classifications at cellular resolution is expected

and supports the validity of the H&E-guided segmentation.

table(rctd_result_level1$spot_class)

#>

#> reject singlet doublet_certain doublet_uncertain

#> 115 2660 1347 296We then synchronize the deconvolution labels back into our

vhdsub SpatialFeatureExperiment object by

matching cell IDs, ensuring that all components remain properly

aligned.

# Subset to RCTD filtered object for convenience

vhdsub <- vhdsub[, colnames(vhdsub)]

# Here we use match to ensure that we match the cell IDs

vhdsub$cellTypeClass <- rctd_result_level1$spot_class[

match(colnames(vhdsub),colnames(rctd_result_level1))]

vhdsub$cellType <- rctd_result_level1$first_type[

match(colnames(vhdsub), colnames(rctd_result_level1))]

# Double check that the numbers of the cell types is consistent

table(vhdsub$cellType)

#>

#> B_cells Endothelial Fibroblast

#> 497 460 1010

#> Intestinal_Epithelial Myeloid Neuronal

#> 529 547 11

#> Smooth_Muscle T_cells Tumor

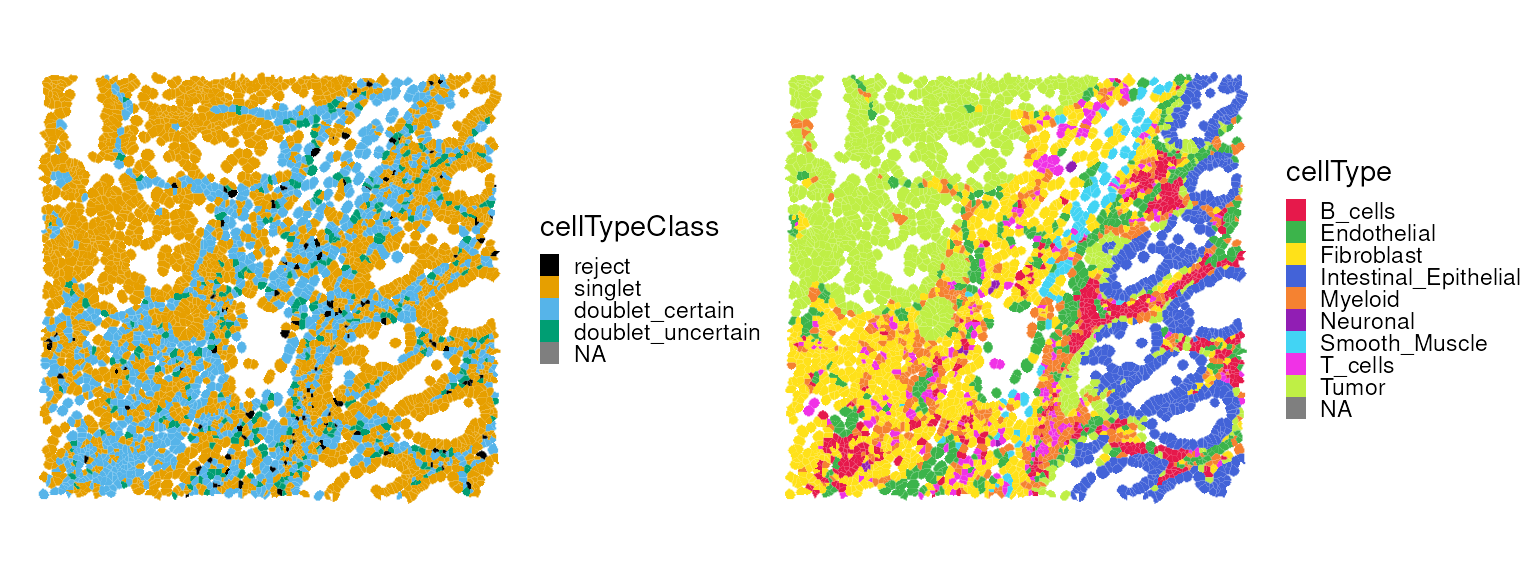

#> 90 262 1012We can visualize the spatial distribution of singlets, doublets, or

the cell types assigned by RCTD.

p0 <- plotSpatialFeature(vhdsub, features = "cellTypeClass",

colGeometryName = "updatecellSeg") +

scale_fill_manual(values = unname(pals::okabe()))

p1 <- plotSpatialFeature(vhdsub, features = "cellType",

colGeometryName = "updatecellSeg") +

scale_fill_manual(values = unname(pals::trubetskoy()))

(p0 | p1) & thin_discrete_legend

Previously, we identified a cell that was flagged as a local outlier

by SpotSweeper. We can now examine its properties in more

detail.

table(vhdsub$subsets_mt_percent_outliers == TRUE)

#>

#> FALSE TRUE

#> 4418 1

vhdsub$cellType[vhdsub$subsets_mt_percent_outliers == TRUE]

#> [1] "T_cells"

vhdsub$cellTypeClass[vhdsub$subsets_mt_percent_outliers == TRUE]

#> [1] doublet_uncertain

#> Levels: reject singlet doublet_certain doublet_uncertainFilter out low-quality cells from the

SpatialFeatureExperiment object prior to performing spatial

clustering.

vhdsub <- vhdsub[, !vhdsub$discard]

dim(vhdsub)

#> [1] 18132 4406Spatial domain identification

First, we identify highly variable genes (HVGs) within the target region. Note that spatially variable genes (SVGs) could be used as an alternative.

vhdsub <- logNormCounts(vhdsub)

dec <- modelGeneVar(vhdsub)

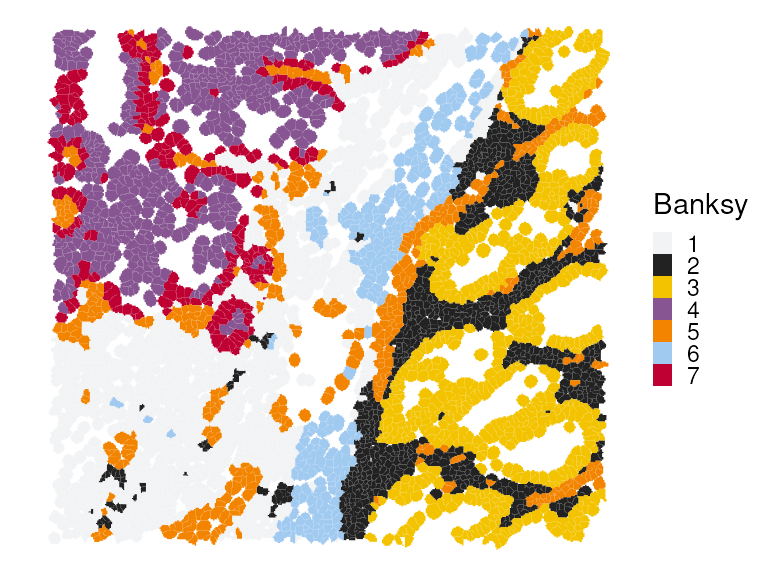

hvg <- getTopHVGs(dec, n=3e3)Banksy

Banksy utilizes a pair of spatial kernels to capture gene expression variation, followed by dimension reduction and graph-based clustering to identify spatial domains.

# restrict to selected features

tmp <- vhdsub[hvg, ]

# compute spatially aware 'Banksy' PCs

set.seed(1000)

tmp <- computeBanksy(tmp,

assay_name = "logcounts",

coord_names = c("array_row", "array_col"),

k_geom = 8) # consider first order neighbors

tmp <- runBanksyPCA(tmp,

lambda = 0.2, # use little spatial information,

npcs = 20)

reducedDim(vhdsub, "PCA") <- reducedDim(tmp)

set.seed(1000)

tmp <- Banksy::clusterBanksy(tmp, lambda = 0.2, npcs = 20, resolution = 0.8)

vhdsub$Banksy <- tmp$clust_M0_lam0.2_k50_res0.8

table(vhdsub$Banksy)

#>

#> 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

#> 1287 844 700 560 471 281 263We can now visualize the clustering results spatially.

plotSpatialFeature(vhdsub, features = "Banksy",

colGeometryName = "updatecellSeg") +

scale_fill_manual(values = unname(pals::kelly())) +

thin_discrete_legend

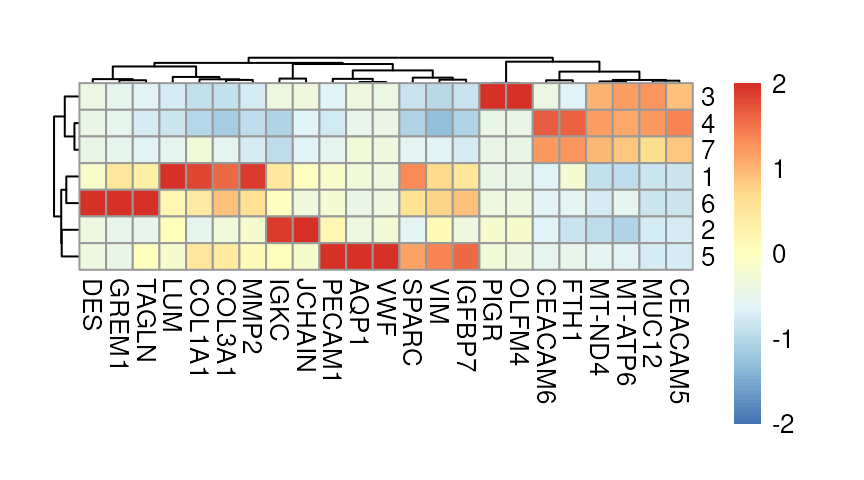

Next, we perform differential gene expression (DGE) analysis to identify marker genes for each cluster. We also compute the cluster-wise mean expression of selected markers.

# differential gene expression analysis

mgs <- findMarkers(vhdsub, groups = vhdsub$Banksy, direction = "up")

# select for a few markers per cluster

top <- lapply(mgs, \(df) rownames(df)[df$Top <= 2])

top <- unique(unlist(top))

# average expression by clusters

pbs <- aggregateAcrossCells(vhdsub,

ids = vhdsub$Banksy, subset.row = top,

use.assay.type = "logcounts", statistics = "mean")Marker genes for each cluster can be visualized using a heatmap.:

# visualize averages z-scaled across clusters

exec(pheatmap,

mat = t(assay(pbs)), scale = "column", breaks = seq(-2, 2, length = 101),

!!!common_args_heatmap)

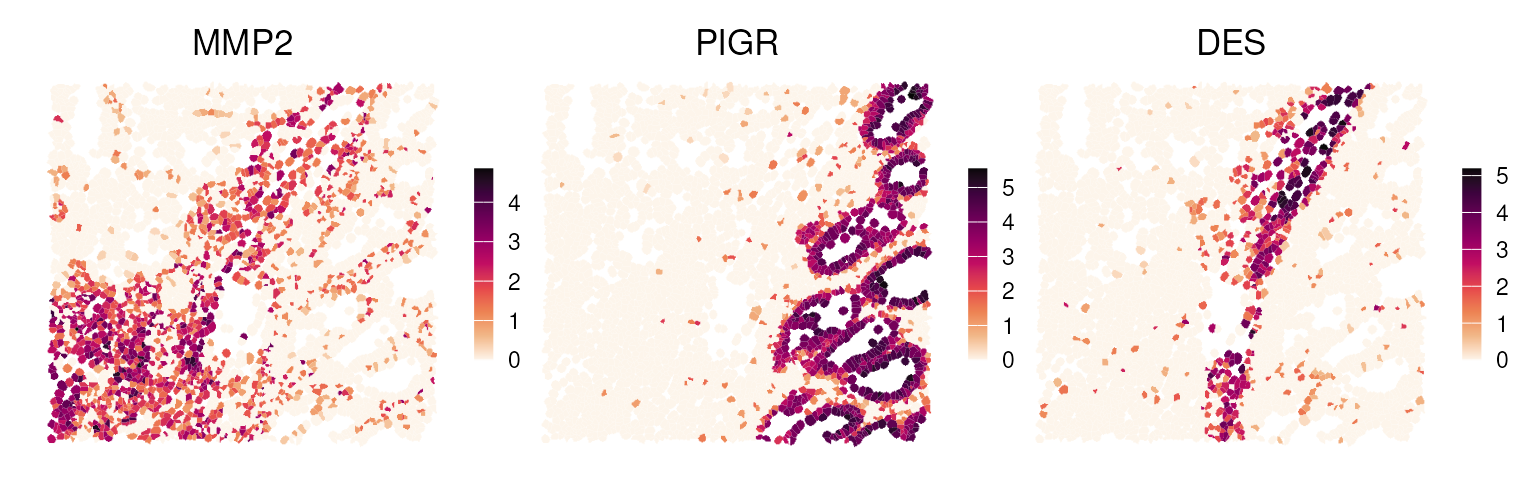

Here, we highlight selected marker genes from clusters 1, 3, and 6, and also visualize their expression patterns in a spatial context:

p0 <- plotSpatialFeature(vhdsub, features = "MMP2",

colGeometryName = "updatecellSeg") + ggtitle("MMP2")

p1 <- plotSpatialFeature(vhdsub, features = "PIGR",

colGeometryName = "updatecellSeg") + ggtitle("PIGR")

p2 <- plotSpatialFeature(vhdsub, features = "DES",

colGeometryName = "updatecellSeg") + ggtitle("DES")

(p0 | p1 | p2) &

gradient_theme &

scale_fill_gradientn(colors = rev(hcl.colors(9, "Rocket")))

Concordance of deconvolution & clustering

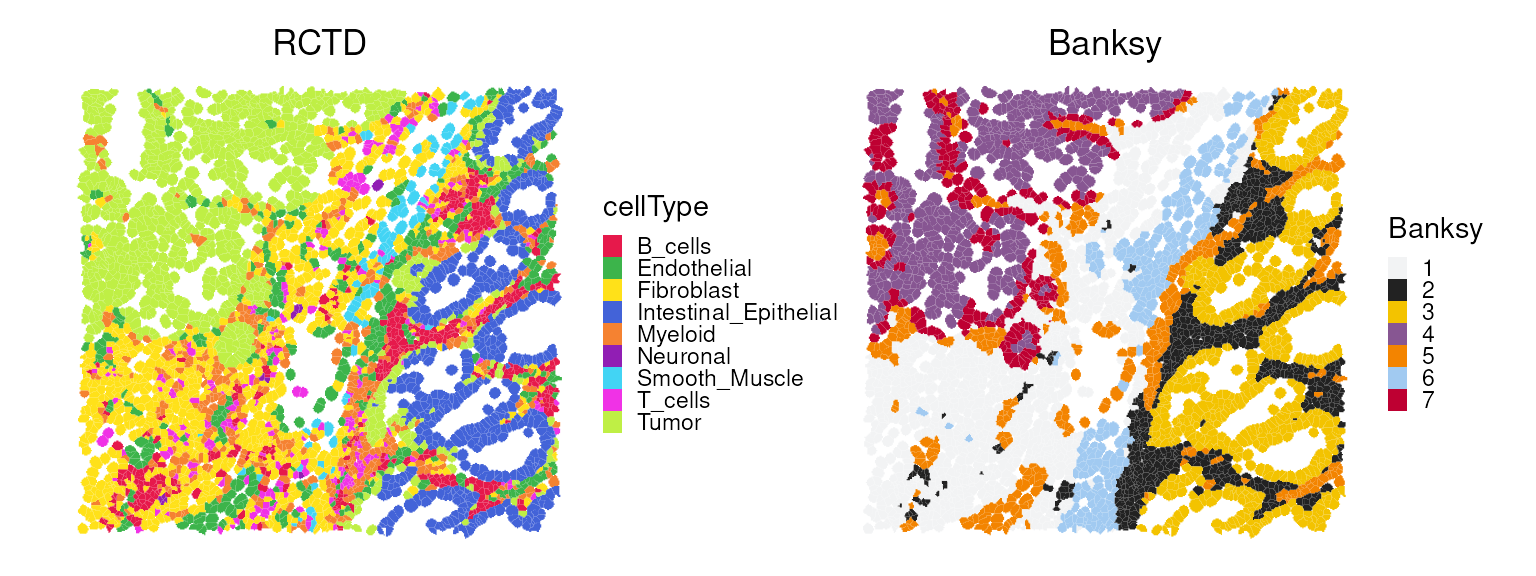

Here, we juxtapose the spatial plots of the deconvolution and clustering results.

p0 <- plotSpatialFeature(vhdsub, features = "cellType",

colGeometryName = "updatecellSeg") +

scale_fill_manual(values = unname(pals::trubetskoy())) +

ggtitle("RCTD")

p1 <- plotSpatialFeature(vhdsub, features = "Banksy",

colGeometryName = "updatecellSeg") +

scale_fill_manual(values = unname(pals::kelly())) +

ggtitle("Banksy")

p0 + p1 +

plot_layout(nrow=1) &

center_title & thin_discrete_legend

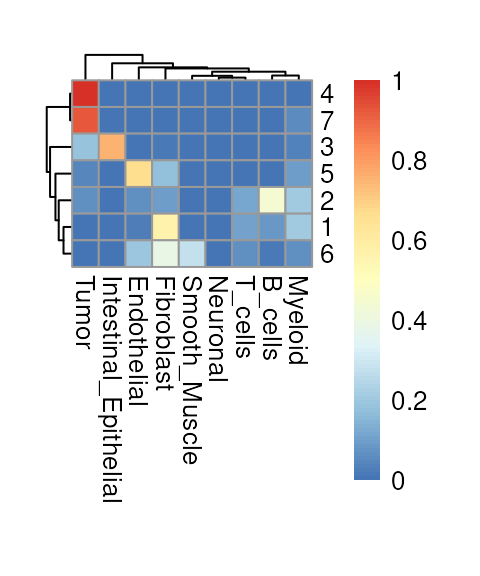

We observe that Banksy delineates tissue boundaries

effectively, while RCTD provides direct biological insight

into the underlying clusters. The concordance between the two methods

can be visualized using a heatmap:

fq <- prop.table(table(vhdsub$Banksy, vhdsub$cellType), 1)

exec(pheatmap, fq, !!!common_args_heatmap)

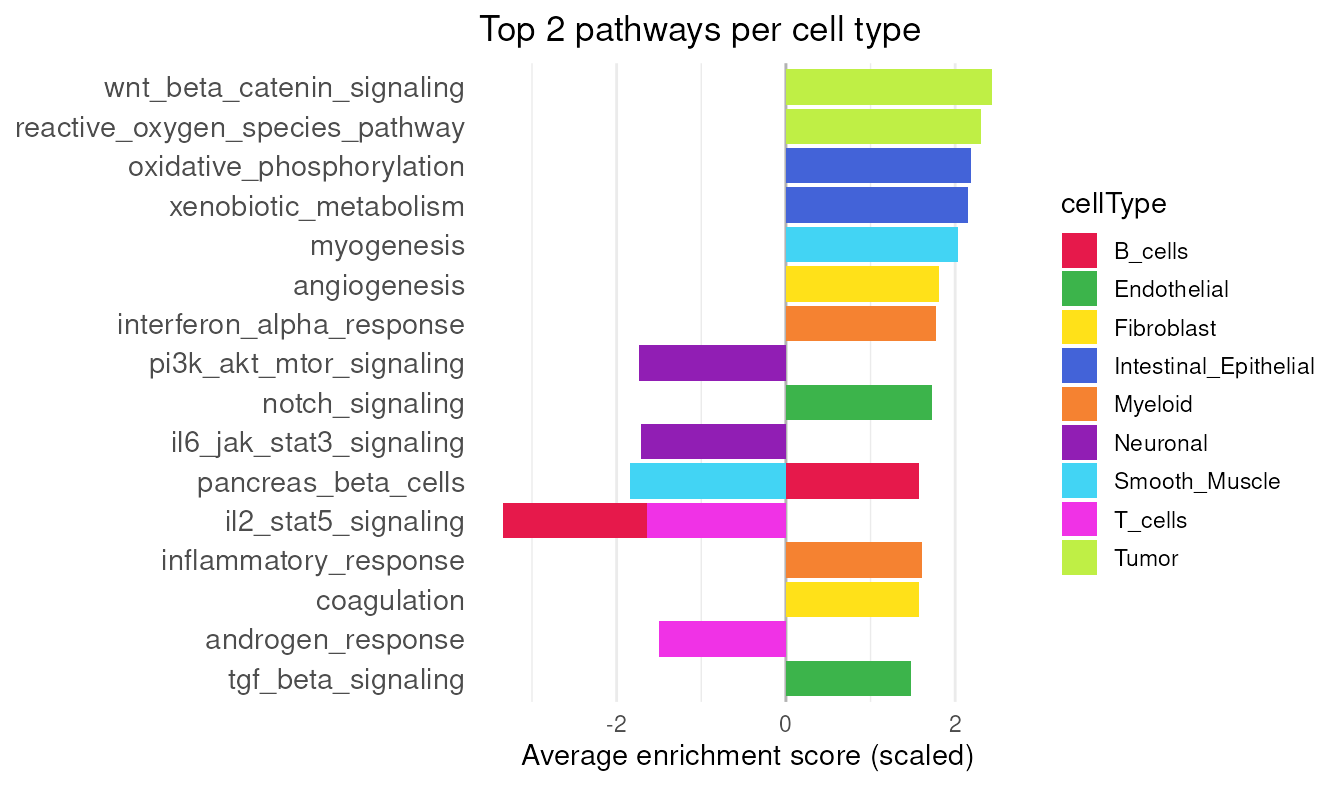

Feature-set signatures

Individual biomarkers identified in the DGE step may or may not have direct phenotypic relevance. Instead, we can quantify gene sets that are known to orchestrate biological functions or pathways, such as metabolic activity, cell cycle progression, and cell death, at the single-cell level.

MSigDB provides a programmatic interface to the Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB) (Subramanian et al. (2005)), one of the largest curated collections of molecular signatures and pathways. We begin by retrieving the human Hallmark gene set collection.

# retrieve & simplify hallmark gene sets from 'MSigDB'

db <- msigdbr(species="Homo sapiens", collection="H")

gs <- split(db$ensembl_gene, db$gs_name)

names(gs) <- tolower(gsub("HALLMARK_", "", names(gs)))Next, we score these gene sets using AUCell (Aibar et al. (2017)), a rank-based approach that (i) ranks genes for each cell and (ii) computes the area under the recovery curve (AUC) for each gene set.

# realize (sparse) gene expression matrix

mtx <- as(logcounts(vhdsub), "dgCMatrix")

# use ensembl identifiers as rownames

rownames(mtx) <- rowData(vhdsub)$ID

# filter for genes represented in panel

.gs <- lapply(gs, intersect, rownames(mtx))

# keep only those with at least 5 genes

.gs <- .gs[sapply(.gs, length) >= 5]

# build per-cell gene rankings

rnk <- AUCell_buildRankings(mtx, plotStats=FALSE, verbose=FALSE)

# calculate AUC for each gene set in each cell

auc <- AUCell_calcAUC(geneSets=.gs, rankings=rnk, verbose=FALSE)A heatmap can be used to examine which signatures are highly expressed in each cell type. To diversify the visualization, we instead summarize the top two signatures per cell type and display their scaled average enrichment scores in a waterfall plot.

# aggregate AUC values by cellType

mu <- aggregateAcrossCells(auc, ids=vhdsub$cellType,

use.assay.type="AUC", statistics="mean")

mu_row_scaled <- rowScale(mu)

top_mu <- getTopSigDF(mu_row_scaled, top_n = 2)

plotDivergentBar(top_mu)

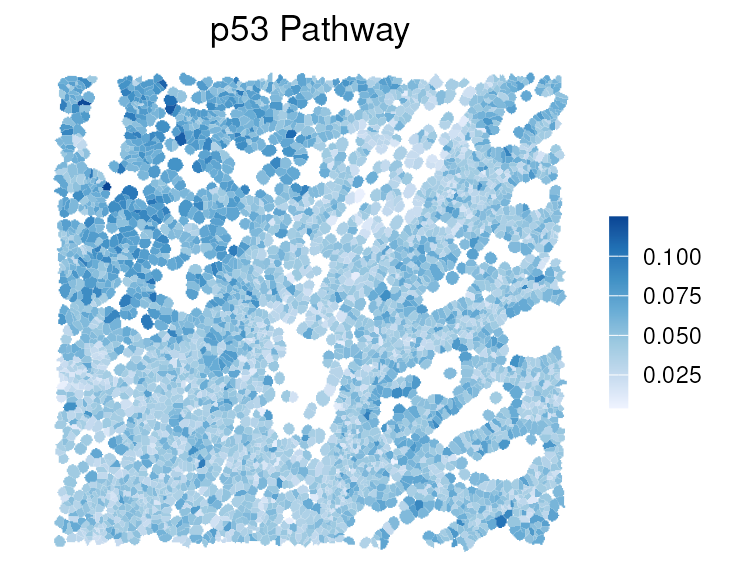

p53 is a well-known pathway involved in tumor cell growth (Vogelstein et al. (2000)), and its enrichment score can be visualized spatially.

# add results as cell metadata

colData(vhdsub)[rownames(auc)] <- t(assay(auc))

plotSpatialFeature(vhdsub, feature = "p53_pathway",

colGeometryName = "updatecellSeg") + gradient_theme +

ggtitle("p53 Pathway")

Shape statistics

Because cell segmentation polygons are available for each cell, we can derive a wide range of shape metrics (Gunz et al. (2025)). sosta was originally developed to analyze multi-cellular anatomical structures using polygons that outline regions of cells; here, we extend its use to investigate the geometry of individual cells.

# get cell segmentations

cellpo <- colGeometry(vhdsub, "updatecellSeg")

cellpo$cellType <- vhdsub$cellType

# get shape metrics

shme <- totalShapeMetrics(cellpo)

shme[1:3, 1:3]

#> cellpo1 cellpo2 cellpo3

#> Area 1067.8050000 854.2350000 2558.400000

#> Compactness 0.7758488 0.4156039 0.521787

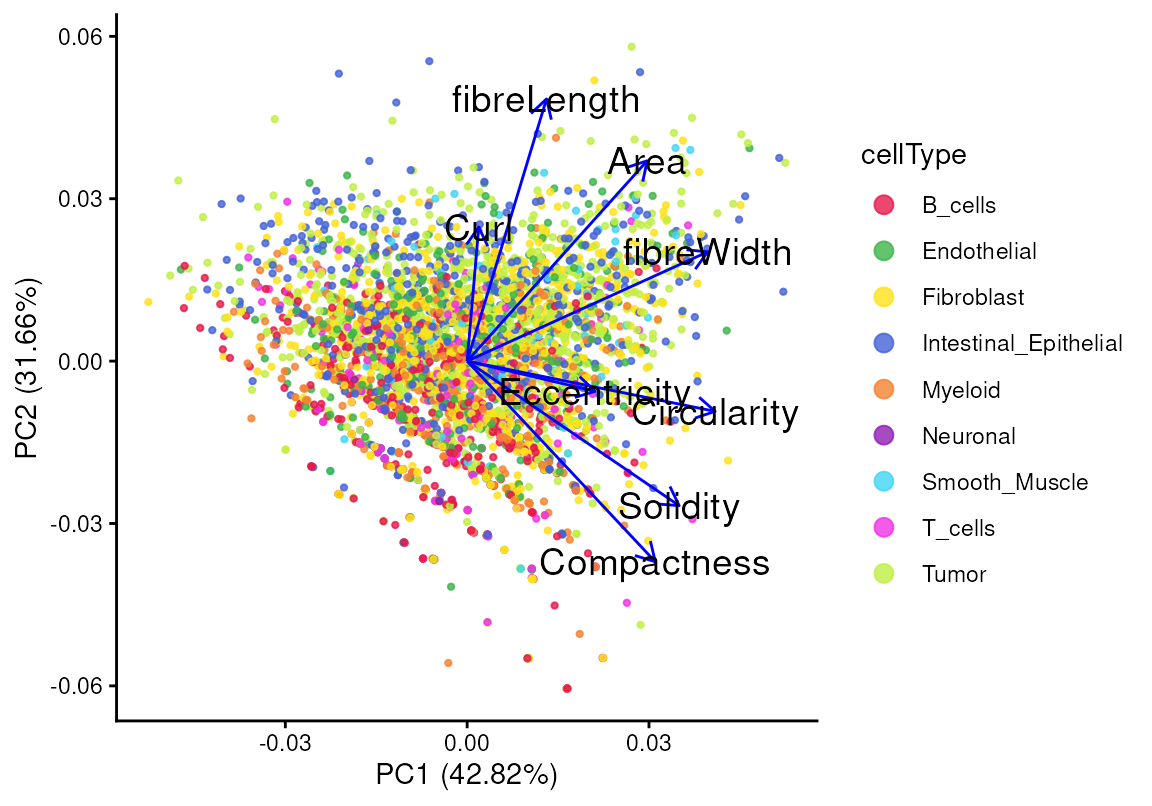

#> Eccentricity 0.8027392 0.5734005 0.740000Here we can check the relationship between shape metrics in the first two principal components (PCs):

tshme <- t(shme) |> as.data.frame()

autoplot(

prcomp(tshme, scale. = TRUE),

data = cellpo,

color = "cellType",

size = 0.8, alpha = 0.8,

loadings.colour = "blue",

loadings.label = TRUE,

loadings.label.size = 5,

loadings.label.colour = "black") +

scale_color_manual(values=unname(pals::trubetskoy())) +

theme_classic() + enlarge_legend_dot

The first principal component (PC1) explains 42.82% of the

variability in the shape statistics, and the second principal component

(PC2) captures 31.66%. The angle between two shape metrics reflects

their degree of similarity, while the length of a loading indicates the

strength of a given metric. For example, the loadings of

fibreLength and Compactness are nearly

perpendicular, indicating a weak or negative correlation between them,

which is consistent with their relationship in the scatter plot. We can

also color the points by the log gene expression of PIGR, a

common epithelial marker, as shown previously. Cells with high

PIGR expression tend to exhibit longer

fibreLength, with no obvious association with

compactness.

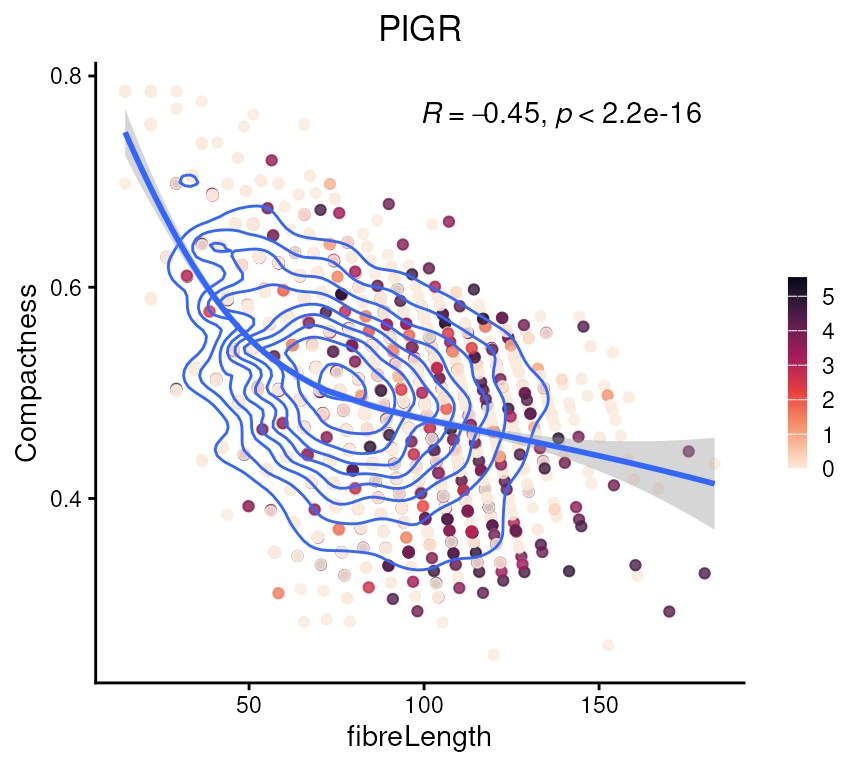

tshme$logPIGR <- logcounts(vhdsub)["PIGR", ]

ggplot(tshme, aes(x = fibreLength, y = Compactness)) +

geom_point(aes(color = logPIGR), alpha = 0.8) +

scale_color_viridis_c(option = "rocket", direction = -1) +

geom_density2d() +

geom_smooth(method='loess', formula= y~x) +

stat_cor(method = "pearson", label.x.npc = "center", label.y.npc = "top") +

theme_classic() + gradient_theme + ggtitle("PIGR")

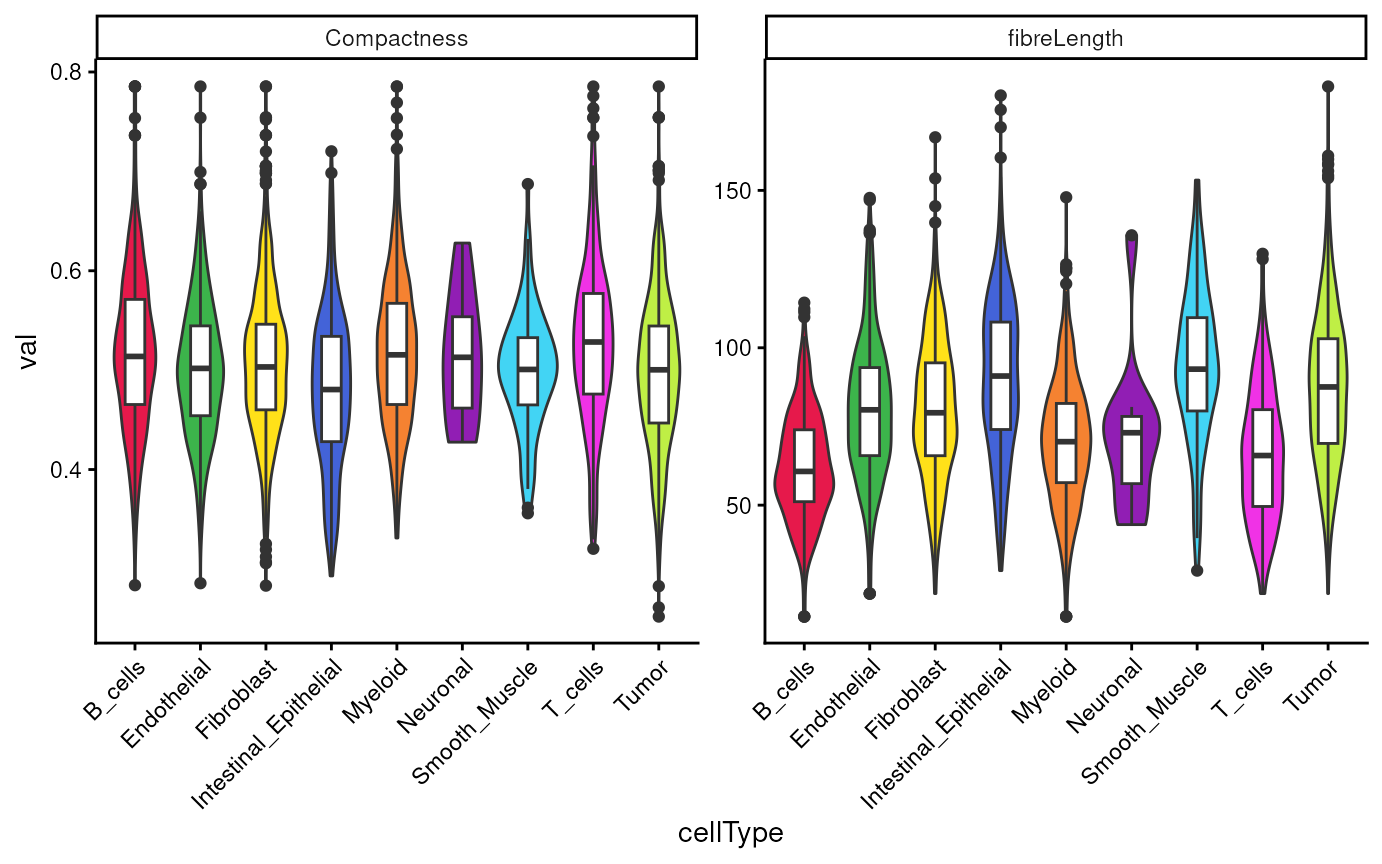

Next, we can summarize the shape statistics per cell type. We check

the differences in fibreLength and Compactness

across cell types.

tshme |>

cbind(cellType = vhdsub$cellType) |>

pivot_longer(cols = -cellType, names_to = "metrics", values_to = "val") |>

filter(metrics %in% c("Compactness", "fibreLength")) |>

ggplot(aes(x = cellType, y = val, fill = cellType)) +

geom_violin() +

geom_boxplot(aes(fill = NULL), width = 0.3) +

facet_wrap(~metrics, scales = "free") +

scale_fill_manual(values = unname(pals::trubetskoy())) +

theme_classic() +

theme(axis.text.x = element_text(angle = 45, hjust = 1)) +

guides(fill = "none")

We observe more uniform distribution in Compactness,

while more variability in fibreLength across cell

types.

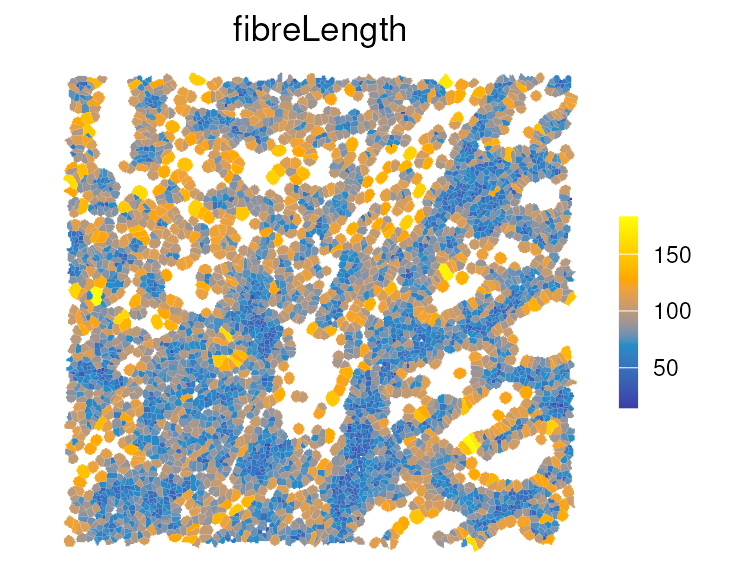

We can also view these shape metrics, such as

fibreLength, spatially:

colData(vhdsub)[names(tshme)] <- tshme

plotSpatialFeature(vhdsub, features = "fibreLength",

colGeometryName = "updatecellSeg") +

scale_fill_gradientn(colors = c("#3B3EA8", "#278EC8", "orange", "yellow")) +

gradient_theme + ggtitle("fibreLength")

For example, immune cells have shorter fibreLength

compared to tumor and stromal cells, which is also shown in the boxplot

above.

Interrogating the spatial arrangement of our cells.

What makes spatial transcriptomics more powerful than scRNA-seq is its integration with spatial statistics. Measures of spatial association are commonly classified as either global or local.

Global spatial association

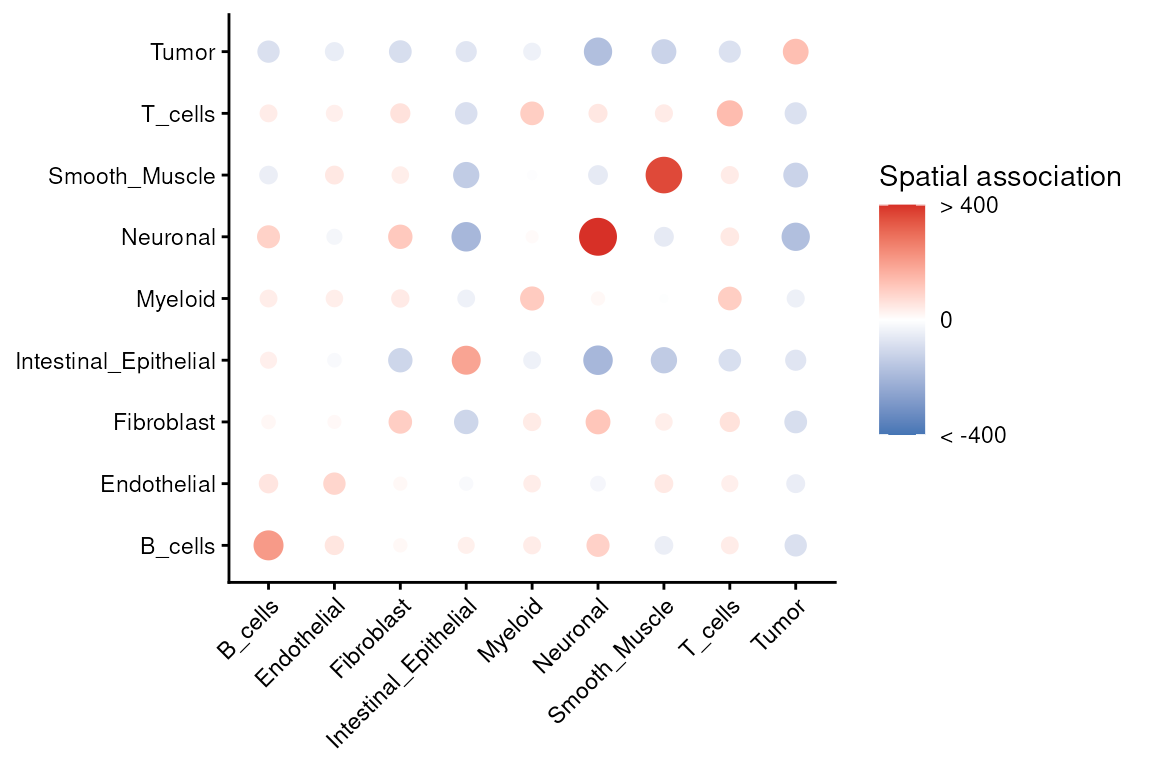

Next, we quantify spatial proximity between annotated cell types. The

getPairwise() function from the spicyR

package computes the K-cross function for all pairs of cell types,

summarizing whether cells of type A tend to occur within a distance

r of cells of type B more frequently than expected under

spatial randomness. Here, we use a radius of 200 units (~50 microns) to

capture immediate neighborhood effects, corresponding to roughly one to

two cell diameters.

crossK = getPairwise(vhdsub,

r = 200,

cellType = "cellType",

imageID = "sample_id",

spatialCoords = c("pxl_col_in_fullres",

"pxl_row_in_fullres"))We can visualize these relationships using

imageCrossPlot(), which displays spatial enrichment and

avoidance across all cell-type pairs. This overview is useful for

scanning for strong interactions before exploring specific pairs in more

detail. To aid interpretation, note the sign of the values: those above

zero indicate spatial attraction at radius r (more

co-occurrence than expected), while values below zero indicate spatial

repulsion.

imageCrossPlot(crossK, limits = c(-400,400)) + gradient_theme +

ggtitle("Spatial association") +

theme(axis.line = element_blank(), axis.ticks = element_blank())

We can revisit the spatial composition of cell types annotated by

RCTD to build intuition for these statistics. This helps

confirm that strong pairwise signals are visible in the tissue image and

are not driven by a handful of cells.

Local indicator of spatial association - LISA

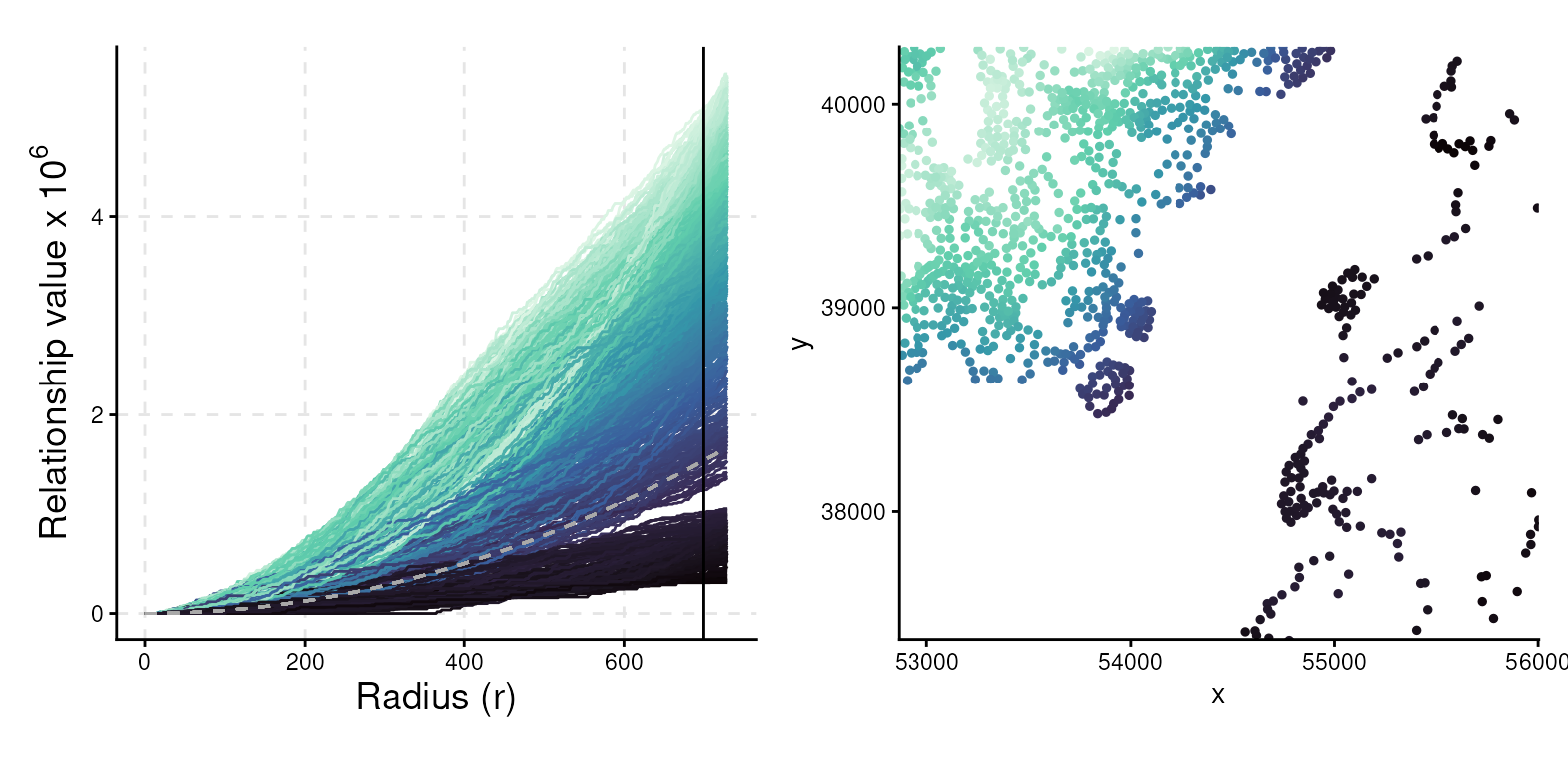

Visium HD cell-level data can be modeled as a point pattern process (Emons et al. (2025)). In contrast to the global average measures described above, local indicators of spatial association (LISA) quantify the local contribution of each cell (Anselin (1995)). First, we construct a plotting data frame containing the LISA Ripley’s K values for tumor cells only.

df <- .speToDf(vhdsub)

pp <- .dfToppp(df, marks="cellType")

# subset to only Tumor cells

ppSub <- subset(pp, marks %in% "Tumor")

# calculate LISA K curves

resLocal <- localK(ppSub, verbose=FALSE)

# code adapted from

# https://robinsonlabuzh.github.io/pasta/01-imaging-univar-ppSOD.html

df <- resLocal |>

as.data.frame() |>

pivot_longer(cols = starts_with("iso"), names_to="curve")

sel <- df |>

filter(r > 700.5630 & r < 702.4388) |>

mutate(sel=value) |>

select(curve, sel)

plt_df <- left_join(df, sel)

head(plt_df)

#> # A tibble: 6 × 5

#> r theo curve value sel

#> <dbl> <dbl> <chr> <dbl> <dbl>

#> 1 0 0 iso0001 0 4642842.

#> 2 0 0 iso0002 0 4042413.

#> 3 0 0 iso0003 0 4173456.

#> 4 0 0 iso0004 0 4113007.

#> 5 0 0 iso0005 0 2766533.

#> 6 0 0 iso0006 0 4535711.Plot the LISA Ripley’s K value for each tumor cell, colored by its value at a radius of 700 pixels. Curves above the gray line that represents complete spatial randomness (CSR) indicate highly clustered tumor cells in the right spatial plot.

p <- ggplot(plt_df, aes(r, value, group=curve, col=sel)) +

geom_line() +

geom_line(aes(y=theo), linetype=2, col="darkgray") +

geom_vline(xintercept=700) +

scale_color_viridis_c(option = "mako") +

xlab("Radius (r)") +

scale_y_continuous(breaks = c(0, 2e6, 4e6), labels = c("0", "2", "4"),

name = bquote("Relationship value x"~10^6)) +

theme_classic() +

theme(legend.position="none",

axis.title = element_text(size=14),

panel.grid.major = element_line(colour = "grey90", linetype = 2))

q <- ggplot(sel %>% cbind(data.frame(x = ppSub$x, y = ppSub$y)),

aes(x, y, col=sel)) +

coord_equal(expand=FALSE) +

geom_point(size=1) +

scale_color_viridis_c(option = "mako") +

theme_classic() + theme(legend.position = "none")

p | q

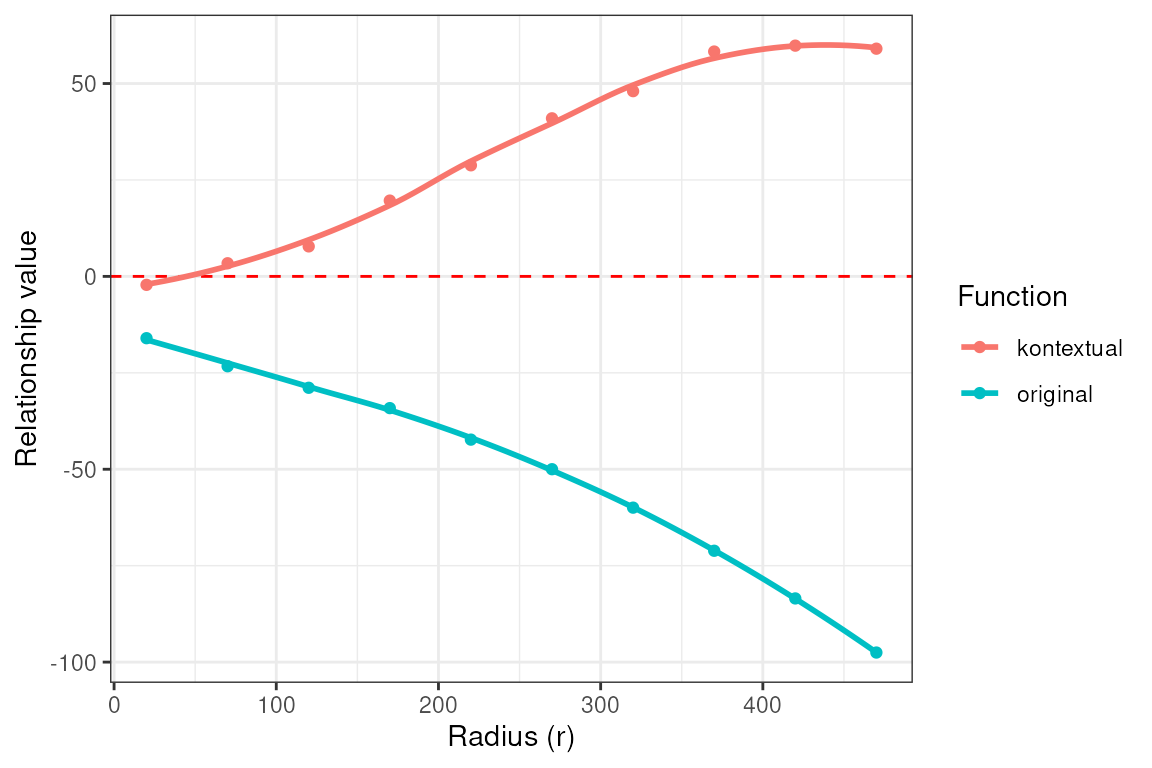

Localisation in context

While pairwise proximity statistics provide a sensible first step,

they can sometimes be misleading because they ignore the broader tissue

context. For example, the K-cross function from spicyR

indicates whether two cell types are found close together more often

than expected under a random distribution, but it does not address

conditional questions. Biologists, however, are often interested in

questions such as:

“Are there certain immune cells that cluster more tightly with tumor cells, after accounting for the fact that immune cells generally do not cluster with tumors?”

This is where Kontextual, from the Statial

package, becomes useful. Kontextual goes beyond pairwise

enrichment by constructing a contextual null model. Rather than

comparing two cell types against a fully random distribution, it

compares the observed association to what would be expected given the

local mixture of neighboring cell types. In practice, this means that

Kontextual tests whether a particular association is

stronger or weaker than expected given the surrounding cellular

environment.

For this demonstration, we define an immune context composed of T

cells, myeloid cells, and B cells. Kontextual then

evaluates whether, within this immune backdrop, specific pairs (for

example, myeloid–tumor) show evidence of additional attraction or

repulsion at a chosen spatial scale. The method is flexible: any

grouping of interest can be defined as a “parent” or context, allowing

conditional relationships of a population to be interrogated relative to

that context.

## Create a vector saying which cells are in the immune context

immune <- c("T_cells", "Myeloid", "B_cells")

## Define the parents we want to use as contexts

parentDf <- parentCombinations(

all = unique(vhdsub$cellType),

immune = immune)

## Run Kontextual with radius of 20

resultsKontextual <- Kontextual(

cells = vhdsub,

parentDf = parentDf,

imageID = "sample_id",

cellType = "cellType",

spatialCoords = c("pxl_col_in_fullres", "pxl_row_in_fullres"),

r = 200

)Let’s visualize the results.

plotKontext <- resultsKontextual |>

ggplot(aes(original, kontextual, label = test)) +

geom_point() +

geom_hline(yintercept = 0) +

geom_vline(xintercept = 0) +

theme_classic()

ggplotly(plotKontext)We can then inspect radius-dependent curves (for example, Myeloid cells around Tumor cells) to determine the spatial scales at which the effect emerges, which is often informative for processes such as invasion fronts or peritumoral niches.

curves <- kontextCurve(

cells = vhdsub, rs = seq(20, 500, 50),

from = "Tumor", to = "Myeloid", parent = immune, se = TRUE,

image = "sample01", cellType = "cellType", imageID = "sample_id"

)

p <- kontextPlot(curves) + theme_classic() +

scale_color_manual(labels = c("Kontextual", "L-Function"),

values = c("#00BE70", "darkblue")) +

scale_fill_manual(values = c("lightgreen", "lightblue")) +

theme(panel.grid.major = element_line(colour = "grey90", linetype = 2),

legend.position = "top",

legend.text = element_text(size = 13),

axis.title = element_text(size = 14))

p@layers$geom_hline$aes_params$colour <- "black" # update dashed line color

p$layers[["geom_ribbon"]]$show.legend <- FALSE # remove geom ribbon box

p

At a global level, the negative L-function values suggest that

Myeloid and Tumor cells are spatially segregated. However, the positive

Kontextual values indicate that Myeloid cells cluster more

strongly with Tumor cells than would be expected given their immune

context (i.e., relative to other immune cells).

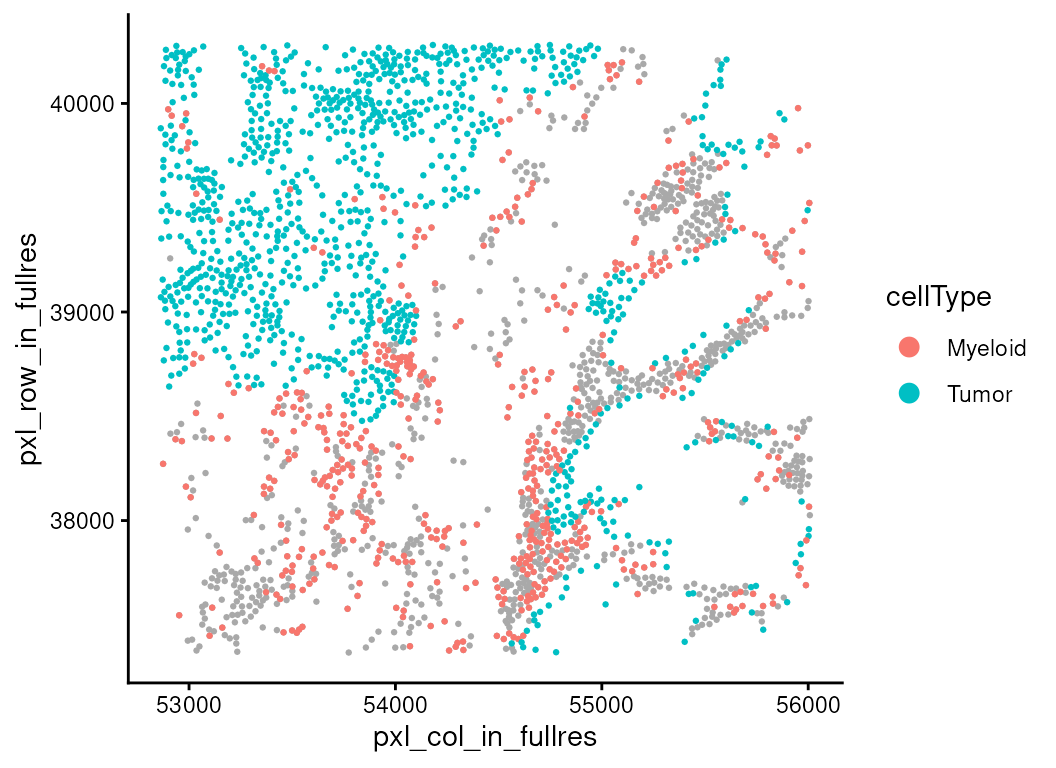

To aid interpretation, we can also re-plot the spatial map with the immune context shown in gray and the two focal cell types highlighted in color. This helps link the statistical findings to tangible spatial patterns within the tissue.

ct_interest <- c("Myeloid", "Tumor")

vhdsub$myetu <- ifelse(!(vhdsub$cellType %in% ct_interest),

"Other", vhdsub$cellType)

vhdsub$myetu <- factor(vhdsub$myetu, levels = c(ct_interest, "Other"))

plotSpatialFeature(vhdsub, features = "myetu",

colGeometryName = "updatecellSeg") +

scale_fill_manual(name = "cellType",

values = c("Myeloid" = "#f58231", "Tumor" = "#bfef45",

"Other" = "grey90")) +

thin_discrete_legend

Identifying expression changes associated with cell localisation

Spatial proximity tells us where different cell types are relative to one another, but an equally important question is what happens to those cells when they are in close contact. Proximity alone does not guarantee functional interaction. To uncover biological relevance, we need to test whether changes in the microenvironment are associated with measurable shifts in gene expression within a given cell type.

This is the motivation behind spatioMark, part of the

Statial package. The idea is simple:

take a target population (for example, Myeloid cells),

quantify its local environment (how many Tumor cells, T cells, Fibroblasts, etc. are nearby within a certain radius),

and ask whether the transcriptomes of the target cells vary with that environment.

In practice, spatioMark first computes local abundances

of each cell type around every cell, giving each cell a numerical

“neighborhood profile.” These covariates then feed into a gene-wise

regression model. For each gene expressed in the target population,

spatioMark fits a generalized linear model. As we have

count data in this case, we leverage functionality in the

edgeR package to model the data as negative binomial. The

coefficients tell us whether gene expression increases or decreases as

the abundance of a chosen neighbor rises.

Abundance

First, we need to quantify the abundance of each cell type around each cell.

vhdsub <- getAbundances(vhdsub,

r = 200,

cellType = "cellType",

imageID = "sample_id"

)Next, we focus on whether Myeloid cells show distinct expression patterns when they are located close to Tumor cells.

stateChanges <- calcStateChanges(

cells = vhdsub,

type = "abundances",

from = "Myeloid",

to = "Tumor",

test = "nb",

imageID = "sample_id"

)

stateChanges |> head(20)

#> imageID primaryCellType otherCellType marker coef tval

#> 1 sample01 Myeloid Tumor IGHG3 -0.26986581 -18.176051

#> 2 sample01 Myeloid Tumor SPP1 0.11458632 13.630583

#> 3 sample01 Myeloid Tumor MMP11 0.05409721 7.351737

#> 4 sample01 Myeloid Tumor MMP12 0.05773036 6.921257

#> 5 sample01 Myeloid Tumor IL1RN 0.04404694 5.943101

#> 6 sample01 Myeloid Tumor IGHD -0.02380578 -5.875567

#> 7 sample01 Myeloid Tumor CTSB 0.03596732 5.741341

#> 8 sample01 Myeloid Tumor GREM1 -0.05300939 -5.724902

#> 9 sample01 Myeloid Tumor MT-CO1 0.03483848 5.647737

#> 10 sample01 Myeloid Tumor WNT5A 0.03899693 5.637293

#> 11 sample01 Myeloid Tumor PYGB 0.04308331 5.471111

#> 12 sample01 Myeloid Tumor MGP -0.04772709 -5.118931

#> 13 sample01 Myeloid Tumor APOC1 0.03665541 5.096505

#> 14 sample01 Myeloid Tumor CEACAM6 0.03919565 5.091371

#> 15 sample01 Myeloid Tumor PLAU 0.03954202 4.999526

#> 16 sample01 Myeloid Tumor IGKC -0.07047815 -4.912809

#> 17 sample01 Myeloid Tumor MT-CO3 0.03117035 4.901309

#> 18 sample01 Myeloid Tumor KRT23 0.02789161 4.848393

#> 19 sample01 Myeloid Tumor DES -0.04838446 -4.805449

#> 20 sample01 Myeloid Tumor IGHG1 -0.05020400 -4.782172

#> pval fdr

#> 1 3.994157e-74 3.392237e-70

#> 2 1.317335e-42 5.594065e-39

#> 3 9.782363e-14 2.769387e-10

#> 4 2.238265e-12 4.752396e-09

#> 5 1.398403e-09 2.375328e-06

#> 6 2.106995e-09 2.982451e-06

#> 7 4.696492e-09 5.493550e-06

#> 8 5.174661e-09 5.493550e-06

#> 9 8.128685e-09 7.335579e-06

#> 10 8.637206e-09 7.335579e-06

#> 11 2.236116e-08 1.726485e-05

#> 12 1.536358e-07 1.078256e-04

#> 13 1.729906e-07 1.078256e-04

#> 14 1.777415e-07 1.078256e-04

#> 15 2.873572e-07 1.627016e-04

#> 16 4.489043e-07 2.378050e-04

#> 17 4.760020e-07 2.378050e-04

#> 18 6.223286e-07 2.936354e-04

#> 19 7.720243e-07 3.450949e-04

#> 20 8.670557e-07 3.681952e-04The previous output is a ranked list of genes, highlighting markers

that change as Myeloid cells are near Tumor cells. One of the top genes

on this list is SPP1 which is known to be expressed in

tumor-associated macrophages. A positive coefficient of SPP1

suggests higher expression of SPP1 in Myeloid cells when they

are in areas of high tumour density. We can visualize this relationship

using the plotStateChanges() function.

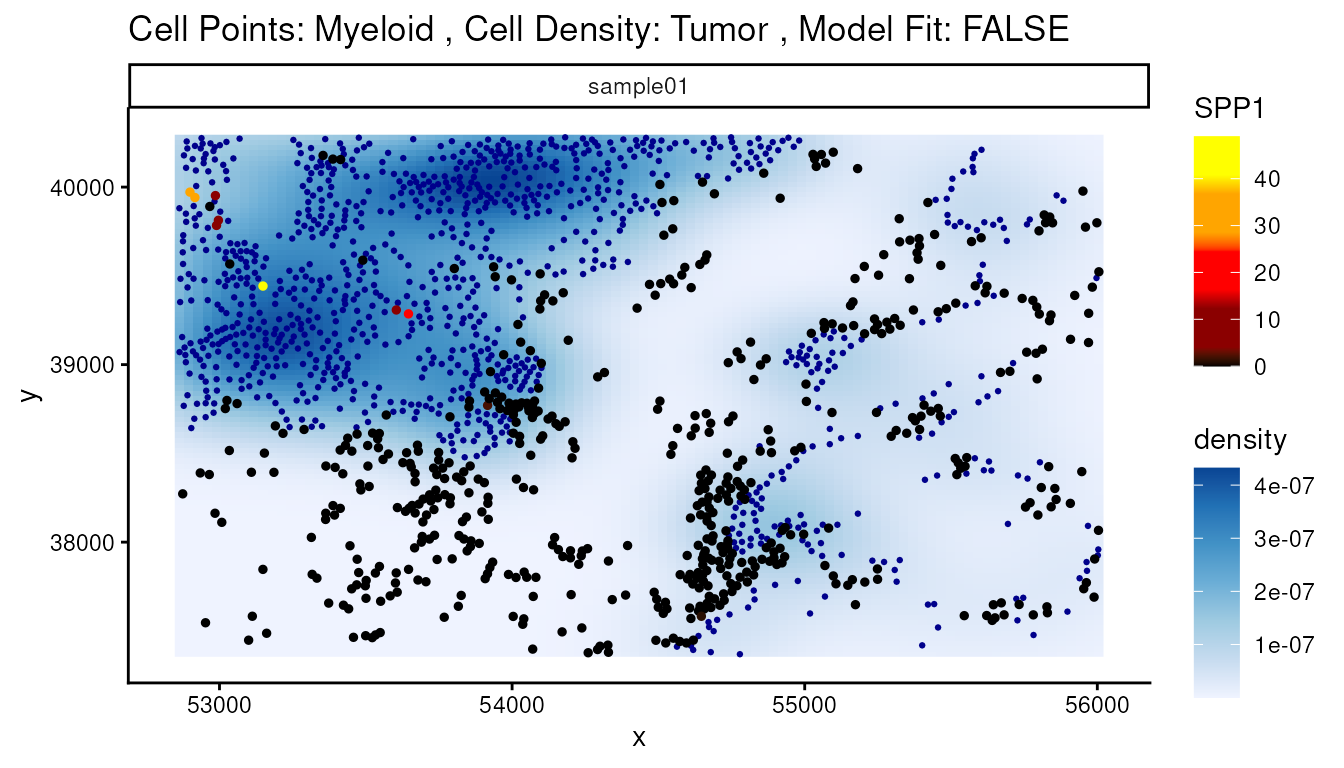

p <- plotStateChanges(

cells = vhdsub,

image = "sample01",

type = "abundances",

from = "Myeloid",

to = "Tumor",

marker = "SPP1",

imageID = "sample_id",

size = 1,

shape = 19,

interactive = FALSE,

method = "lm"

)

p[[1]] + theme_void() +

theme(legend.key.width = grid::unit(0.5, "lines"),

legend.key.height = grid::unit(1, "lines")) + facet_null() +

ggtitle("Cell Points: Myeloid, Cell Density: Tumor") + center_title

Contamination

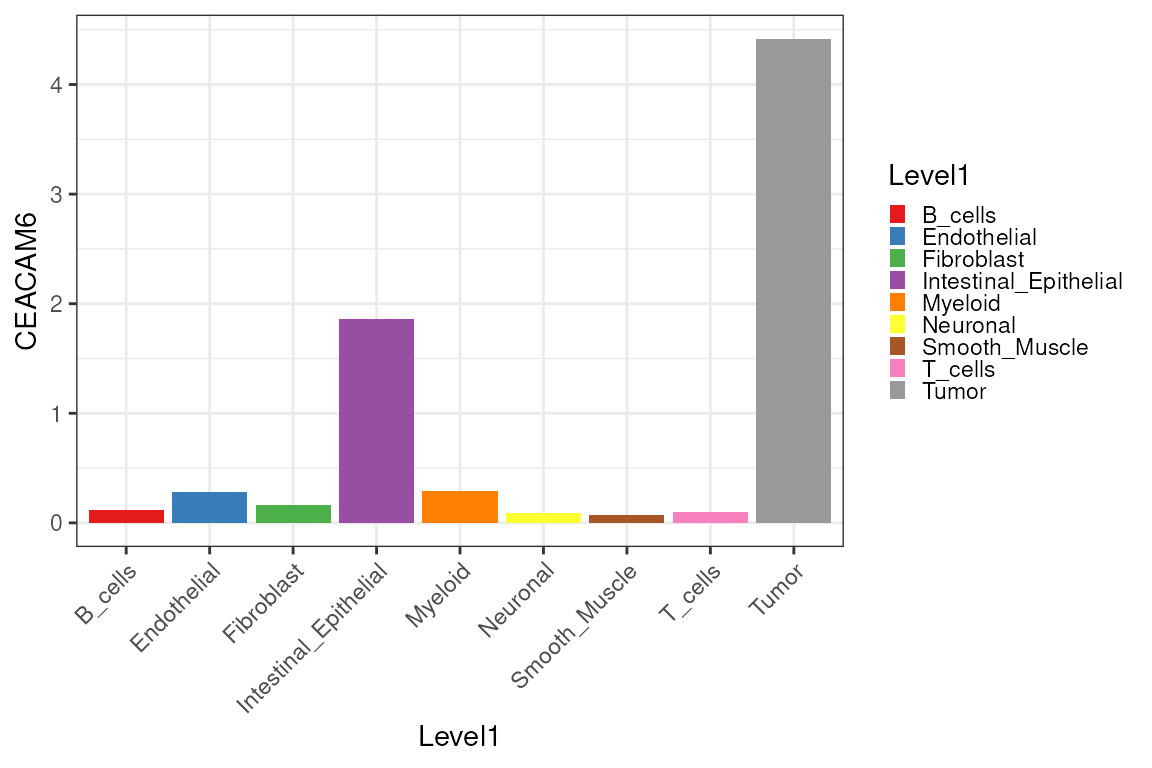

However, some genes should not be expressed in macrophages, such as CEACAM6, and are therefore likely the result of lateral spillover or transcript diffusion.

sce[, down_sample] |>

join_features(features = "CEACAM6", shape = "wide") |>

mutate(logCEACAM6 = log1p(CEACAM6)) |>

ggplot(aes(x = Level1, y = logCEACAM6, fill = Level1)) +

geom_boxplot() +

scale_fill_manual(values = unname(pals::trubetskoy())) +

theme_classic() + ylab("CEACAM6 log expression") +

theme(axis.text.x = element_text(angle = 45, hjust = 1),

legend.position = "none") +

thin_discrete_legend

Because we already computed RCTD weights, we can

mitigate contamination by adding deconvolution-derived components as

covariates to our models. By storing the RCTD cell-type

weight matrix into reducedDim(vhdsub, "RCTD"), we can pass

"RCTD" to the contamination argument of

calcStateChanges(). spatioMark will use these

estimates of contamination in its modelling to hopefully remove false

positives like CEACAM6 while preserving genuine

relationships.

contam <- assay(rctd_result_level1, 1) |>

t() |>

as.matrix() |>

as.data.frame()

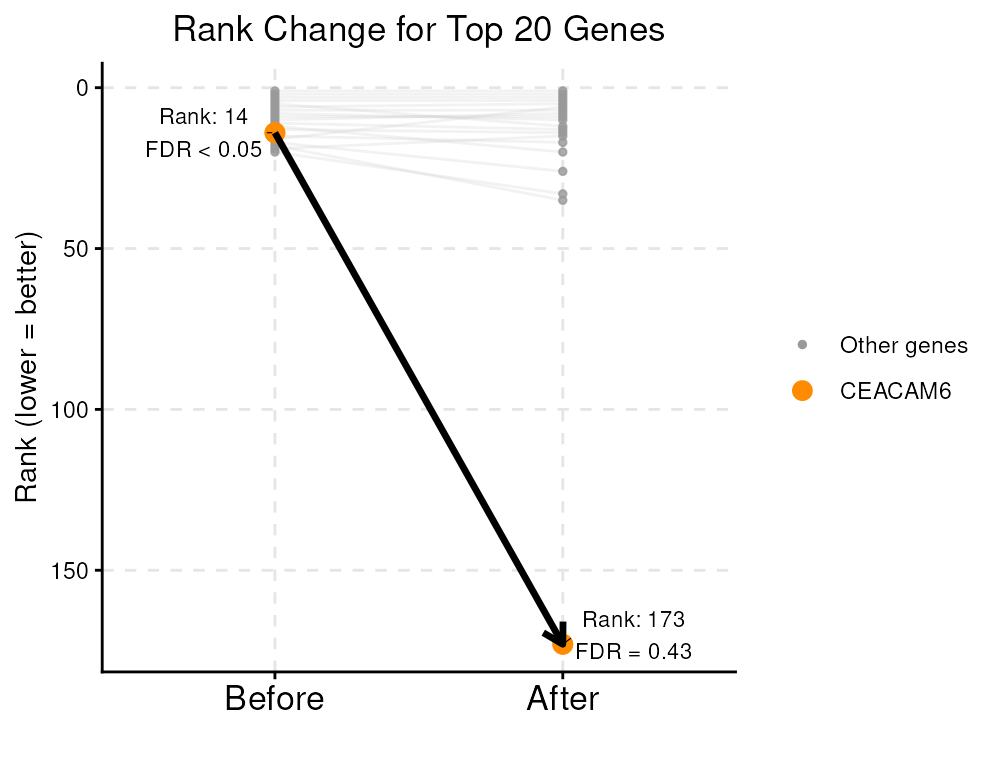

reducedDim(vhdsub, "RCTD") <- contam[match(colnames(vhdsub), rownames(contam)),]After correction, the false discovery rate of CEACAM6 is no longer significant at a threshold of 0.05. The rank of this gene falls from 14 to 173, while other macrophage-relevant top genes, such as SPP1, keep their high rankings and remain contamination-invariant.

stateChangesCon <- calcStateChanges(

cells = vhdsub,

type = "abundances",

from = "Myeloid",

to = "Tumor",

test = "nb",

imageID = "sample_id",

contamination = "RCTD"

)

stateChangesCon |> filter(marker == "CEACAM6")

#> imageID primaryCellType otherCellType marker coef tval pval

#> 1 sample01 Myeloid Tumor CEACAM6 0.0225659 2.376978 0.008727561

#> fdr

#> 1 0.4283528Next, we can visualize the change of ranking of CEACAM6 after decontamination, among the top 20 marker genes as Myeloid cells get near Tumor cells.

plotRankChange(target_gene = "CEACAM6", n = 20, stateChanges, stateChangesCon)

So far, we have analyzed one CRC sample from patient P2. In fact, Oliveira et al. (2025) includes multiple patients in this Visium HD public dataset, spanning different disease conditions (healthy vs. cancer). To apply spatial statistics to assess cell-type colocalization across multiple conditions, you can refer to the Multi-sample chapters of the OSTA book: a. Differential spatial patterns, b. Differential colocalization, c. Structure-based analysis

Extension

You can try using a finer resolution of cell type classified by

RCTD.

Or you can try using a different deconvolution algorithm.

set.seed(1000)

vhd2 <- vhdsub

colnames(spatialCoords(vhd2)) <- c("x", "y")

sce2 <-sce[, down_sample]

counts(vhd2) <- as(counts(vhd2), "sparseMatrix")

counts(sce2) <- as(counts(sce2), "sparseMatrix")

CARD_obj <- CARD_deconvolution(

spe = vhd2,

sce = sce2,

sc_count = NULL,

sc_meta = NULL,

spatial_count = NULL,

spatial_location = NULL,

ct_varname = "Level2",

ct_select = NULL, # decon with all sce$Annogrp cell types

sample_varname = NULL, # use all sce as one ref sample

mincountgene = 0,

mincountspot = 0

)

# a matrix/data.frame of probabilities per cell (rows) × cell types (cols)

P <- CARD_obj$Proportion_CARD[colnames(vhdsub), ]

# cell type with the largest probability in each row

vhdsub$cellType2 <- colnames(P)[max.col(P, ties.method = "first")]

reducedDim(vhdsub, "CARD") <- as.data.frame(P)